Books |

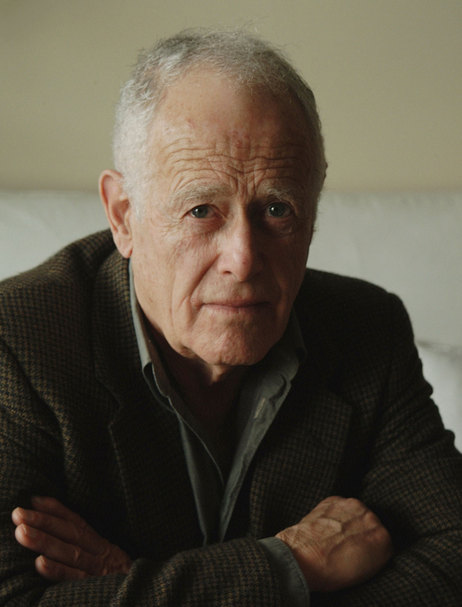

James Salter (1925-2015)

By

Published: Apr 22, 2019

Category:

Fiction

June 19, 2015. I was playing poker with my wife and daughter at midnight in Paris — we couldn’t sleep, and we were using potato chips for chips, and there was a light breeze coming through the large windows, and I think we were all as happy and in-the-moment as a family can be — when my email bell rang. Jill Krementz. From New York. That morning, Salter had gone to the gym in Bridgehampton, dropped to the floor, and died. “Last words” didn’t apply.

Salter had died once before, when 32-year-old James Horowitz decided to end the life he knew — career Air Force pilot, buttoned-up husband and father — and become a writer. There was scant evidence he could succeed as a creator of stories and novels. But there was absolute certainty that he had to do it.

As James Salter, he invented a distinctive style, built on the integrity of the sentence. To Hemingway’s muscularity he added feminized insight; the result was prose that was as deeply emotional as it was taut and exact.

“She had a face now that was for the afterlife and those she would meet there.”

“She was a creature of blue, flawless days, the sun of their noons hot as the African coast, the chill of the nights immense and clear.”

“… glasses still with dark remnant on them, coffee stains, and plates with bits of hardened Brie.”

The sentences drop, regular as coins. The cadences are hypnotic. But Salter didn’t create that style to provoke admiration — his sentences are arrows to the real subject of these stories, which are, like the best stories about adult men and women, about honor and love in the face of death.

His breakthrough came in 1967, with the publication of A Sport and a Pastime, a short novel about the unlikely romance of a Yale dropout and a French shop girl in a small town. No one writes about France more lovingly than Salter; read a few paragraphs and you’ll want to buy a ticket. Not to Paris, though Salter gets its late nights and parties perfectly, but to the “real” France, where the smell of wood smoke is in the air and life is played out to the rhythm of seasonal change.

“Soon we are rushing along an alley of departure, the houses of the suburbs flashing by, ordinary streets, apartments, gardens, walls. The secret life of France, into which one cannot penetrate, the life of photographs albums, uncles, names of dogs that have died. And in ten minutes, Paris is gone. The horizon, dense with buildings, vanishes. Already I feel free.”

Cool prose, every word chosen, re-considered, affirmed. Mannered? Only until you get used to it. Then the world falls away and the book itself dissolves, and you are taken over by its characters.

Two reviews in The New York Times praised “A Sport and a Pastime” — Reynolds Price called it “as nearly perfect as any American fiction I know,” Webster Schott described it as “a tour de force in erotic realism.” But the eroticism was unsettling, the book thin, the publisher nervous. It became a “cult classic.”

Joe Fox, a legendary editor at Random House, was once asked which of the books he worked on would be called “great” long after their reviews were compost. There were two, he said. One was “In Cold Blood,” by Truman Capote. The other was James Salter’s novel, Light Years, for which Random paid Salter $7,500. That 1975 novel is considered his masterpiece. Now, that is. At publication, a New York Times reviewer called the main characters “insulting to our patience and our expectations.” Another said the novel was “overwritten, chi-chi and rather silly.” Reviews like that do not boost sales. But readers who weren’t put off by characters named Viri and Nedra quickly formed the Cult of Salter, and word-of-mouth built an audience for Salter’s writing.

Short story collections followed: Dusk and Last Night. Isaac Babel famously said that “No iron can strike the heart with as much force as a period in exactly the right place.” That is why I’m particularly fond of the stories in “Last Night,” a master class in fiction.

“He didn’t make much money, as it turned out. He wrote for a business weekly. She earned nearly that much selling houses. She had begun to put on a little weight. This was a few years after they were married. She was still beautiful — her face was — but she had adopted a more comfortable outline.”

Whew. That was fast. And efficient: “This was a few years after they were married.”

In these stories, privileged women pine for love — or sex. At a man’s funeral, there are women the widow has never seen before. A married man is having an affair with a male friend. A hill is made from a pile of junked cars. A romantic opportunity is missed.

There was a memoir at once lacerating and tender: Burning the Days. A delightful book about food with his wife, Kay Eldridge: Life Is Meals. In 2013, he was feted for his first novel in three decades, All That Is.

Salter had large hopes for this book. And it did make the Times list — for a week. But, as usual, his satisfactions were personal and private. “Redford phoned yesterday,” he wrote in an email. “He was in the south of France taking a break after all the business of the opening of his movie. He wanted to tell me how much he loved ‘All That Is.’ He went on for a while — I’m omitting the details out of modesty. He’d read it a second time, he said. He might even read it a third.”

Which is what you get when you are, as was so often said: “a writer’s writer.” Like this:

Two years after his death, a welcome collection: Don’t Save Anything: Uncollected Essays, Articles, and Profiles. The pieces were worth saving. Consider these gems:

From a profile of a climber: “Molly Higgins is a lab technician in a hospital. She has blond hair and the decent American face of the girl in the emergency room who is there when your eyes open and you love her from then on.”

“Fellini had black hair growing out of his ears, like an unsuccessful uncle.”

“I liked her generosity and lack of morals — they seemed close to an ideal condition of living.”

Charlotte Rampling: “I was to learn many things about her: that she chewed wads of gum, had dirty hair, and, according to the costume woman, wore clothes that smelled. Also that she was frequently late, never apologized, and was short-tempered and mean.”

“There was wreckage all around, but it was like the refuse piled behind restaurants: I did not consider it — in front they were bowing and showing me to a table.”

“Once we passed a big Alfa Romeo that she recognized as belonging to a friend, the chief of detectives in Rome. She had made love with him, of course. ‘Darling,’ she said, ‘There’s no other way. Otherwise there would have been terrible trouble about my passport. It would have been impossible.’”

“There remains, in the case of those years in the movies, a kind of silky pollen that clings to the fingertips and brings back what was once pleasurable, too pleasurable, perhaps — the lights dancing on dark water, as in the old prints, the sound of voices, laughter, music, all faint, alluring, far off.”

And finally….

“There is something called the true life, which I cannot describe and which perhaps varies as one sees it from different angles and at different times. At one point it is travel, at another a certain woman, at another a house somewhere with a view you will worship till you die. It is a life apart from money and to the side of ambition, a life lived in one way or another for beauty. It does not last indefinitely, but the survivors are usually not poorer for it.”

You read lines like that with almost physical pleasure. And with pen in hand, marking, sometimes envious, always admiring.

In 2013, he wrote me: “These days I am feeling how much I’d like to begin again, not from the very beginning but somewhere about a third of the way in.” That would make him about 60, his age when we met.

Because I always think of my friends as the age they were when we first countered one another, it’s hard think of James Salter as gone. Indeed, even when “All That Is” was described as a summing up, I preferred to write about this relatively thick novel as a prelude to the next book. And I see him now, eternally young, always looking ahead, surrounded by notebooks, turning words this way and that, struggling to write, not his final book, but his best one, aiming as ever for the only immortality worth having.

But let Salter have the last word:

“Somewhere the ancient clerks, amid stacks of faint interest to them, are sorting literary reputations. The work goes on endlessly and without haste. There are names passed over and names revered, names of heroes and of those long thought to be, names of every sort and level of importance.”

For his readers, his name and work couldn’t be more important.

BONUS RECIPE

Figs in Whiskey

1 package dried figs, Turkish or Greek seem best

2 cups sugar

1 1/2 cups Scotch whiskey

Boil the figs for 20 minutes in about a quart of water in which the sugar has been dissolved. Allow to cool until tepid. Drain half the remaining water or a bit more and add the Scotch. Allow to steep a good while in a covered bowl before serving.