Books |

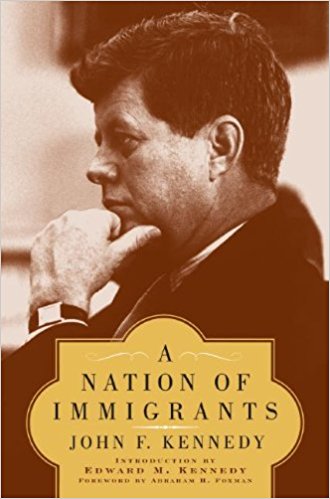

John F. Kennedy: A Nation of Immigrants

By

Published: Apr 08, 2018

Category:

History

“Once I thought to write a history of the immigrants in America. Then I discovered that the immigrants were American history.”

– Oscar Handlin, in “The Uprooted,” winner of a Pulitzer Prize in 1952

For a book I’m writing, I’ve read 30 books about John F. Kennedy, but I didn’t know he had written a book about immigration until I read a recent article in the Times that announced the government’s revision of its mission statement on this hot-button subject:

The federal agency that issues green cards and grants citizenship to people from foreign countries has stopped characterizing the United States as “a nation of immigrants.”

The director of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services informed employees in a letter on Thursday [February 1, 2018] that its mission statement had been revised to “guide us in the years ahead.” Gone was the phrase that described the agency as securing “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants.”

The agency director, L. Francis Cissna, who was appointed by the Trump administration, described the revision as a “simple, straightforward statement” that “clearly defines the agency’s role in our country’s lawful immigration system and the commitment we have to the American people.” Mr. Cissna did not mention in his letter that he had removed the phrase “nation of immigrants.”

Kennedy published “A Nation of Immigrants” in 1958, when he was a Senator. A cynic might say that he was looking ahead to the 1960 Presidential election. In fact, this was an issue he cared about — in 1963, as President, he sent Congress a proposal for legislation that would “liberalize” immigration statutes. [That proposal is one of several appendices.]

This short (51 pages of text) book is as timely now as it was then. And a great argument-starter. I can’t think of a book more likely to annoy some Americans: Kennedy, liberal, immigration, all in one sentence. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Kennedy wrote the book for the One Nation Library, a project of the Anti-Defamation League. In 1958, much of America was prosperous and smug; the appetite for change and inclusion wasn’t large. And the shadow of Joe McCarthy had not quite faded. It took some courage to publish a book that viewed immigrants compassionately — indeed, as heroic.

But here was young Kennedy, beginning his book with de Tocqueville’s description of America as a society of immigrants [see the excerpt, below] and moving on to describe what it was like to come to America in the 19th century. Average trip from Liverpool to New York: 40 days. In many vessels you couldn’t stand up straight if you were taller than 5’5”. One in 10 immigrants died during the crossing.

Kennedy presents a short history of the reasons for immigration — religious persecution, political oppression and economic hardship. He takes the reader through immigration before 1776; post-Revolution, he presents the contributions of specific nationalities and the “new tensions” that flared when the immigrants spoke no English or were slow to learn.

The most interesting section for this reader explored the thicket of “private immigration bills” — legislation that dealt with cases that would ordinarily be rejected. In one session of Congress, he notes, some 3,500 of those bills were introduced — about half of the legislation. The cases are infuriating: a European college girl convicted for putting slugs in a pay phone, now married to an American teacher, but unable to come here because of her criminal record. An Italian woman convicted of stealing bundles of sticks to build a fire. And the quotas! Andorra, with 6,500 citizens, had an annual immigration allotment of 100; Spain, then with 28 million people, had a quota of only 250.

One value of the book is to remind us that Kennedy, for all his pragmatism, had some causes he really cared about. But more, “A Nation of Immigrants” shows the noble and generous people we sometimes claim to be — and the narrow-minded, short-sighted and outright cruel people we often are. It’s almost comforting to know this strain in American politics and culture wasn’t recently minted.

======

EXCERPT: Chapter One

A Nation of Nations

On May 11, 1831, Alexis de Tocquevile, a young French aristocrat, disembarked in the bustling harbor of New York City. He had crossed the ocean to try to understand the implications for European civilization of the new experiment in democracy on the far side of the Atlantic. In the next nine months, Tocqueville and his friend Gustave de Beaumont traveled the length and breadth of the eastern half of the continent—from Boston to Green Bay and from New Orleans to Quebec—in search of the essence of American life.

Tocqueville was fascinated by what he saw. He marveled at the energy of the people who were building the new nation. He admired many of the new political institutions and ideals. And he was impressed most of all by the spirit of equality that pervaded the life and customs of the people. Though he had reservations about some of the expressions of this spirit, he could discern its workings in every aspect of American society—in politics, business, personal relations, culture, thought. This commitment to equality was in striking contrast to the class-ridden society of Europe. Yet Tocqueville believed “the democratic revolution” to be irresistible.

“Balanced between the past and the future,” as he wrote of himself, “with no natural instinctive attraction toward either, I could without effort quietly contemplate each side of the question.” On his return to France, Tocqueville delivered his dispassionate and penetrating judgment of the American experiment in his great work Democracy in America. No one, before or since, has written about the UnitedStates with such insight. And, in discussing the successive waves of immigration from England, France, Spain and other European countries, Tocquevile identified a central factor in the American democratic faith:

All these European colonies contained the elements, if not the development, of a complete democracy. Two causes led to this result. It may be said that on leaving the mother country the emigrants had, in general, no notion of superiority one over another. The happy and powerful do not go into exile, and there are no surer guarantees of equality among men than poverty and misfortune.

To show the power of the equalitarian spirit in America, Tocqueville added: “It happened, however, on several occasions, that persons of rank were driven to America by political and religious quarrels. Laws were made to establish a gradation of ranks; but it was soon found that the soil of America was opposed to a territorial aristocracy.”

What Alexis de Tocqueville saw in America was a society of immigrants, each of whom had begun life anew, on an equal footing. This was the secret of America: a nation of people with the fresh memory of old traditions who dared to explore new frontiers, people eager to build lives for themselves in a spacious society that did not restrict their freedom of choice and action.

Since 1607, when the first English settlers reached the New World, over 42 million people have migrated to the United States. This represents the largest migration of people in all recorded history. It is two and a half times the total number of people now living in Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont and Wyoming.

Another way of indicating the importance of immigration to America is to point out that every American who ever lived, with the exception of one group, was either an immigrant himself or a descendant of immigrants.

The exception? Will Rogers, part Cherokee Indian, said that his ancestors were at the dock to meet the Mayflower. And some anthropologists believe that the Indians themselves were immigrants from another continent who displaced the original Americans—the aborigines.

In just over 350 years, a nation of nearly 200 million people has grown up, populated almost entirely by persons who either came from other lands or whose forefathers came from other lands. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt reminded a convention of the Daughters of the American Revolution, “Remember, remember always, that all of us, and you and I especially, are descended from immigrants and revolutionists.”

Any great social movement leaves its mark, and the massive migration of peoples to the New World was no exception to this rule. The interaction of disparate cultures, the vehemence of the ideals that led the immigrants here, the opportunity offered by a new life, all gave America a flavor and a character that make it as unmistakable and as remarkable to people today as it was to Alexis de Tocqueville in the early part of the nineteenth century. The contribution of immigrants can be seen in every aspect of our national life. We see it in religion, in politics, in business, in the arts, in education, even in athletics and in entertainment. There is no part of our nation that has not been touched by our immigrant background. Everywhere immigrants have enriched and strengthened the fabric of American life. As Walt Whitman said,

These States are the amplest poem,

Here is not merely a nation but

a teeming Nation of nations.

To know America, then, it is necessary to understand this peculiarly American social revolution. It is necessary to know why over 42 million people gave up their settled lives to start anew in a strange land. We must know how they met the new land and how it met them, and, most important, we must know what these things mean for our present and for our future.