Books |

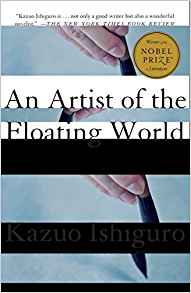

Kazuo Ishiguro: “An Artist of the Floating World”

By

Published: Feb 05, 2019

Category:

Fiction

GUEST BUTLER BARBARA FINKELSTEIN is the author of Summer Long-a-coming. Her pieces for Head Butler include In Defense of Long Books, The Phantom Tollbooth, and The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. She is at work on a book about mental illness and housing in the Bronx.

—-

The Uber driver who took me from Krakow to Auschwitz a few years ago told me about a former classmate who had an unfair advantage. “In Nazi times, his grandfather robbed a Jewish family,” he said. “Today my classmate drives a Lexus and lives on his ‘family estate.’”

Nearly 75 years had passed since that opportunistic grandpa benefited from the murder of his Jewish neighbors — and the matter was still real for my thirtysomething driver. This is exactly the never-ending post-war consciousness that Kazuo Ishiguro recreates brilliantly in “An Artist of the Floating World,” the 1986 novel that helped to bring him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017. Ono, the novel’s sixty-something narrator, asks, in so many words, if it’s fair, in, say, 1948, to judge the way people behaved in 1942 — when their war-time conduct resulted in the suffering, even death, of innocent people. [To buy the paperback, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Ono, for one, feels pretty good about himself. Early in the novel he tells us he was able to buy his beautiful home because of his “moral conduct and achievement” — not because he made useful friends during the German-Japanese alliance. “I have never at any point in my life been very aware of my social standing, and even now, I am often surprised afresh when some event, or something someone may say, reminds me of the rather high esteem in which I am held,” Ono tells us.

Right. This grandiose self-analysis sets off alarm bells in your head.

In fact, we get a hint about Ono’s cluelessness when Ono enters into marriage negotiations on his younger daughter’s behalf. Talks with a previous family ended when the groom backed out. Ono concludes that this fellow felt he was inadequate. Ono’s daughter serves as the novel’s skeptical conscience: “I wonder, Father, if it was simply that I didn’t come up to their requirements,” she says. In this novel of hints and allusions, what she means to say is that “we didn’t measure up.” Maybe Ono’s reputation is not quite as esteemed as Ono thinks it is?

Ono’s reputation — whatever it may be — resides in his work as an artist. After resisting his family’s wishes that he study accounting, Ono becomes an acclaimed practitioner of “floating world” art, paintings of geishas that made the Japanese demimonde a fitting subject for Japan’s national pride. Eventually Ono abandons this artistic orthodoxy and takes belligerent lower class boys — a la Hitler Youth? — as his new subject.

In the course of 200 pages, Ishiguro quietly — deftly — reveals that the esteemed Ono has betrayed friends, colleagues and mentors in his quest to create a “new Japan” through his art. Like that grandpa in Poland, Ishiguro’s sweet old Ono is — well, you decide. Do we draw a direct line between Ono’s nationalism and the misery his friends and neighbors endured? Was Ono simply in the right place at the right time? Would you be okay with marrying into his family?