Books |

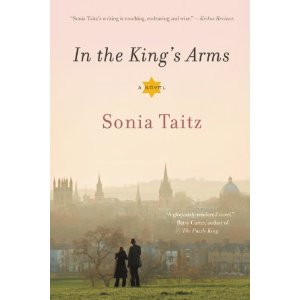

In the King’s Arms

Sonia Taitz

By

Published: Oct 17, 2011

Category:

Fiction

I get many, many new books each week; there’s no way I can be fair to them all. So I developed a plan: I read the first sentence, and if it hooks me, I read the first paragraph. If that appeals, I go on to the first chapter.

But make no mistake: I’m looking to put the book down.

“In the King’s Arms” starts like this: “There was a place for everything, and everything was in its place but Lily.”

Promising. I read on:

She had come to Europe in a great heat, pressing her attentions upon one of its most ancient institutions. To gain access to Oxford she’d had to get “A” after “A” every day of her schoolgirl life, then flag them at Doorkeepers of Western Civilization. Years of sprawling across the desk with outflung arm, pleading to be “called on,” annunciated by the teacher. And later, at college, her perfect papers: “well observed, “ “sensitive.” Lily entertained the idea that she could amount to something spectacular. The Messiah, who had not yet arrived, could well be a woman, particularly in these times.

See a wasted word there? A flat sentence? Me neither. I pressed on. 216 pages later, I was done. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Along the way, I thought often of Evelyn Waugh — the smart talk, the fey Brits, country houses, good clothes, lineage for centuries. And I thought how, as the decades rush by, Waugh increasingly seems to me as remote as…oh, Thomas Hardy. Of course Waugh has successors — the Martin Amis crew — and while I admire their verve and wish I had their effortless eloquence, I find them emotionally chilly. Snotty, really.

What Sonia Taitz has done is, therefore, very appealing. She’s created a young, attractive, brilliant Jewish graduate student from New York’s Lower East Side — the daughter of Holocaust survivors, even — and, in 1975, tossed her into the rarified world of Waugh. This is no Philip Roth Jew who believes the goyim are, if not actually dumb, less bright: “She loved the strength of Renaissance brass, and the moody words ‘heath’ and ‘moor.’

And the English man she meets! Peter Aiken. A smooth talker, of course. On German girls: “They had thickened calves. You’ve heard of ‘the fatted calf,’ haven’t you? Those girls had two, each. Ankles like tree trunks. It’s no wonder they lost the war. No pretties to die for. None that I saw, at any rate. None like you.”

Peter is not The One. On a visit to the country home, where the stuffy stepfather offers Lily “a wee dram” and the disapproving mother fears the worst. Lily meets his brother Julian. (We’re in England, where these things often happen.). Julian makes quite the entrance:

He yelled out suddenly: “Startle easily?”

She jumped in the air, and then she saw him.

He laughed aloud at the pretty confusion in her face.

She joined him, laughing.

“The famous Julian.”;

A page later:

“What is your name?”

“Lily.”

“Are you sure?”

“No….”

“Who am I?”

A moment passed before she answered, eyes wet.

“You’re mine.”

They began kissing blindly.

And now we’re thrust into a love story, rich in complications, richer in echoes — like her parents in the Nazi camps, Lily is out of her element. Happily, Taitz has a light touch; there’s no ponderous organ music underneath these moments, they’re just markers, sign posts of the distance traveled.

Is this just a smart yarn, cleverly told? No. There is a theme: “how a man leaves his family and cleaves to his wife.” But again, it’s not hammered home — here, even the heavy moments have verve and wit.

What makes this more remarkable is how much Sonia Taitz has taken from her own life — and, again, how little she has infused memoir with melodrama. “I have a Bachelor’s degree in English and Psychology from Barnard College, an M.Phil in English literature from Oxford, and a law degree from Yale,” she writes. “My parents, who were immigrants, placed a huge value on education, which no one could ever take away from you.”

She learned her lessons well. Mr. Waugh, move over.