Books |

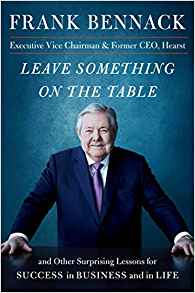

Leave Something on the Table, and Other Surprising Lessons for Success in Business and in Life

Frank Bennack

By

Published: Oct 15, 2019

Category:

Memoir

For the last year I worked with Frank Bennack on his book, “Leave Something on the Table: and Other Surprising Lessons for Success in Business and in Life,” so I can’t responsibly tell you how good this book is. I can, however, explain why I was so eager to help Frank with his book, what I learned along the way, and why this book isn’t like the nutritionally empty CEO books that clog the category.

Frank Bennack is a business legend — he was CEO of Hearst for a mind-boggling 29 years; under his leadership Hearst revenues grew 14 times and earnings increased more than 30 times — but it is entirely possible that his name is unfamiliar to you. There’s a good reason for that: he was too busy doing his job. And heading major boards — like NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Lincoln Center, and The Paley Center for Media.

While Frank was re-inventing Hearst, I was a creature of Condé Nast — I worked for Tina Brown at Vanity Fair, wrote for The New Yorker, House & Garden, Traveler, Glamour, Mademoiselle and Self — and, like many who breathed that air, I thought it was the place to be. We flew the Concorde and Fedexed our luggage. And for the first time in media history, writers were extravagantly well paid.

Like Condé Nast, Hearst is privately owned. But during my time at Condé Nast, the resemblance ended there. Hearst was cheap; as Frank notes in the book, Hearst threw nickels around as if they were manhole covers. And by comparison with Condé Nast, Hearst was dull; with the exception of the reliably outrageous Helen Gurley Brown at Cosmopolitan and some dazzling stories in Esquire, we didn’t see much to get excited about.

At Condé Nast, we completely missed the real story: Frank Bennack was turning a magazine-and-newspaper company into a start-up that would become vastly more successful than its snooty rival. He bought TV stations. He sought out partners. And then lightning struck. One of those partners called Frank and asked if Hearst might like to buy 20 per cent of ESPN, a cable network then featuring tractor pulls. Hearst bought that 20 per cent for $167 million. ESPN is now valued at $30 to $40 billion. It’s not too strong to say that was the deal of the century.

The owners of ESPN could have called anyone. They called Frank. Why? That is the question “Leave Something on the Table” answers. Because the underlying story of this book isn’t how a poor boy from San Antonio scaled the heights and stayed at the top for three decades, it’s something even more remarkable. In a time when more and more CEOs are borderline criminals, Frank Bennack is straight and honest — you could do a deal with him on a handshake. He’s the model of what a leader should be, and not just in business. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audio book, read by the author, click here.]

I once asked one of the Talking Heads why their documentary, “Stop Making Sense,” is so terrific. “Speed,” he said. “We edited it as we shot it — we wanted to finish it before we turned against it.” Writing a book with a CEO can also call for speed — you want to finish before the CEO drops the mask and reveals the egomaniac beneath. But not this time. Now that we’re done, I admire Frank more. I believe you will also admire him — and in this terrible time find some inspiration in his story. Starting from the beginning….

——

The Prologue of “Leave Something on the Table”

This is a book of stories. I was CEO of Hearst for almost three decades, so many of those stories are about business. But the point of telling these stories is not to revisit old challenges, brag about long-ago successes, or explain how, on my watch, we transformed a 1950s magazine and newspaper company into a hundred-year-old start-up.

Although I’m in many of these stories — hey, it’s my book — they’re really about the people in my life, and what I learned from them, and what we accomplished together.

In many of these stories you’ll also meet two remarkable and accomplished women. Luella Mae Smith, my high school girlfriend, became my wife for more than fifty years. She died tragically and without warning on April 17, 2003. She is central to the period from 1949 to 2003. Dr. Mary Lake Polan, to whom I was married on April 2, 2005, has supported me and enriched my life on many levels. She has been an important force throughout my second tour as CEO of Hearst, as well as during my Lincoln Center and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital chairmanships. Like Luella, she has made the good times better and the difficult times bearable.

If these stories offer some wisdom, it’s this: the importance of values in our private lives and work lives — the value of values.

You don’t hear much about values in the business press these days. Mostly you hear about transactions. That’s inevitable. The deals are bigger now. There’s more and louder publicity accompanying them. The claimed benefits generally include a better world—often a better world through technology.

Some of the stories you’ll find in these pages describe transactions that made headlines, but what’s more important, I think, is how and why those transactions happened. Underpinning the business reasons were relationships, some going back for decades. And underpinning those relationships was mutual understanding. It didn’t need to be verbalized— our lives and our businesses were the proof. Under our roofs, people came together, shared a mission, created a culture, and produced superior products. And what connected them? Our shared values.

This will sound quaint to some readers.

Institutional culture and character — building it, maintaining it, passing it on — is a slow process. My parents taught me what is important — honesty, integrity, hard work, concern for other — and that mistakes, and I’ve made my share, can be overcome. My mentors showed me how to build on that foundation. My colleagues and partners led by example. And then our enterprise succeeded beyond our expectations.

We live in a time of the instant trend, the pop-up shop, the product that defines the moment and vaporizes fast. Of course, there are businesses that have experienced meteoric growth because they were first with a good idea; Hearst invested in some and got a nice return. But others puzzle me. How can enormously profitable companies take no responsibility for what appears on their screens? If a company becomes successful by running roughshod over the competition and flaunting its ability to operate outside government regulations, can it really reform itself? And this, most of all: Can a company that runs on algorithms ever acquire human values?

It’s not currently fashionable to make the case for the high road. It looks longer, and old-fashioned, and it’s easy to conclude that while you’re climbing the ladder, burdened by your values, others are reaching the top faster. But if the stories in these pages suggest a broader truth, it’s exactly the opposite: The high road is quicker, with a better view along the way, and more satisfaction at the summit. And you end up loving rather than hating your partners.

I’ve worked for Hearst for more than six decades. I was its leader for twenty-eight years. That makes me a double unicorn — in this century, few will collect gold watches for long service, and fewer will lead businesses for decades. But it’s not just CEOs who are confronting an uncertain future. In this supercharged climate, solid achievement and energetic commitment are no guarantee of continued success; everyone, at every level, in every enterprise, is legitimately anxious. So how are smart, ambitious people to make their way?

I believe there is one unchanging North Star. It isn’t what you know, and how hard you work, and how clever you are. It’s not even who you know. It’s how other people know you. It’s who you are.