Books |

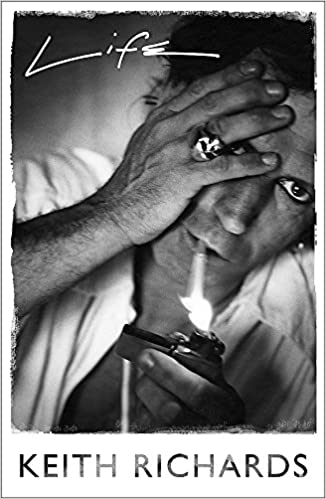

Life

Keith Richards

By

Published: Aug 24, 2021

Category:

Memoir

When I was starting to date someone, I occasionally asked, “Who’s the most important Rolling Stone?” The typical answer, “Mick Jagger, no contest.” Sorry. Charlie Watts was the right answer. (An easy way to tell: Keith often played with his back to the audience because he was playing to and with Charlie.) Talk about an unlikely pair. Charlie was on the Best Dressed list, he was silent, not flashy, it was easy to miss his significance — as someone wrote, “He always looked like a guy that came in through the wrong door and the band asked him to play.” At the Playboy Mansion, he played pool all night rather than break his vow of fidelity to his wife. And he drummed like that: absolute time, with a backbeat kicker.

Could he rip you out of your chair? Crank the volume and listen to the bass drum at the start of “Street Fighting Man.” And the machine gun drumming on “Get Off Of My Cloud.” For chills, watch the Maysles camera hold on his face during the playback of “Wild Horses” — the camera doesn’t blink, and neither does he.

The Times obit is solid and respectful. Indeed, there’s only one recorded story of an agitated Charlie Watts. In 1984, Jagger had a bad case of Lead Singer Syndrome. There was some thought he’d leave the band. One night in Amsterdam, Keith and Mick went out for drinks and more drinks. Keith: “We got back to the hotel about five in the morning and Mick called up Charlie. I said, don’t call him, not at this hour. But he did, and said, ‘Where’s my drummer?’ No answer. He puts the phone down. Mick and I were still sitting there, pretty pissed. About twenty minutes later, there was a knock at the door. There was Charlie. Shaved, in a Savile Row suit and cologne. He didn’t even look at me, he walked straight past me, got hold of Mick and said, ‘Never call me your drummer again. I’m not your drummer. You’re my singer.’ Then he gave Mick a right hook that knocked him across the room.”

Charlie Watts didn’t write a book. That story is from Keith’s memoir. There are a lot more, just as good, in those 600+ pages. If you haven’t read it, a treat awaits.

Keith Richard is the Rolling Stone you notice when Mick Jagger’s not shaking and singing. The one who kicked his heroin addiction by having all his blood transfused in Switzerland. Who was — for ten years in a row — chosen by a music magazine as the rocker "most likely to die." Whose solution to spilling a bit of his father’s ashes was to grab a straw and snort. Who didn’t hesitate to publicize the size of Mick’s penis.

Wild man. Broken tooth, skull ring, earring, kohl eyes — he’s Cpt. Jack Sparrow’s father, lurching though life as if it’s a pirate movie, ready to unsheath his knife for any reason, or none. Got some blow, some smack, a case of Jack Daniels? Having a party? Dial Keith.

When you get a $7 million advance for your memoirs, there’s no such thing as a "bad" image. But the thing about Keith Richards is, he wants to tell the truth. Like: he didn’t have his blood transfused. Like: he didn’t take heroin for pleasure or to nod out, but so he could tamp his energy down enough to work. Like: he and Jagger may not be friends but they’re definitely brothers — and if you talk shit about Mick to him, he’ll slit your throat.

Why does Keith want to undercut his legend?

Because he has much better stories to tell.

And in "Life," the 547-page memoir he wrote with James Fox, he serves them up like his guitar riffs — in your face, nasty, confrontational, rich, smart, and, in the end, unforgettable. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audio CD, click here.]

Start with the childhood. Keith grew up in a gray, down-and-out suburb of London. School: "I hated it. I’d spend the whole day wondering how to get home without taking a beating." By his teens, he’d figured the system out: "There’s bigger bullies than just bullies. There’s them, the authorities." He adopts "a criminal mind, anything to fuck them up." His school record reflects this: "He has maintained a low standard was the six-word summary of my 1959 school report, suggesting, correctly, that I had put some effort into the enterprise."

His mother is his savior. She likes music, and is a "master twiddler" of the knobs on the radio. When he’s 15, she spends ten quid she doesn’t have to buy her only child a guitar. (No spoilers here, but much later in the book, you’re going to fight tears when he plays a certain song for her.)

The rest of the book? Keith Richards and a guitar — and what a love story:

Music was a far bigger drug than smack. I could kick smack; I couldn’t quit music. One note leads to another, and you never know what’s going to come next, and you don’t want to. It’s like walking on a beautiful tightrope.

What music interests him? Oh, come on: the music of the dispossessed — black Chicago blues. Mick Jagger, who lives a few blocks away and is prosperous enough to actually buy a few records, also loves this music. To say they bond is to understate: "We both knew we were in a process of learning, and it was something you wanted to learn and it was ten times better than school."

The Rolling Stones form. The casting is quite funny: "Bill Wyman arrived, or, more important, his Vox amplifier arrived and Bill came with it." An apartment is acquired; think "Animal House." But also think about dedication so complete that "anybody who strayed from the nest to get laid, or try to get laid, was a traitor."

Today bands dream of getting rich. Not the Stones: "We hated money." Their first aim was to be the best rhythm and blues band in London. Their second was to get a record contract. The way to do that was to play.

Something happened when the Stones were on stage, something sexy and dangerous and never seen before. The Beatles held your hand. The Stones — well, as a night watchman said after a concert, "Not a dry seat in the house." In 18 months, the Stones never finished a show. Keith estimates they played, on average, five to ten minutes before the screaming started, and then the fainting, until the security team was piling unconscious teenage girls on the stage like so much firewood.

Fame. When it comes, there’s no way out; you need it to do your work. The Stones at least brought a new look to it; they pissed on the press, didn’t care what the record company wanted. Only the music mattered. As Berry Gordy liked to say, "It’s what’s in the grooves that counts."

"The world’s greatest rock band" — between 1966 and 1973, it’s hard to argue that they weren’t. Songs poured out of them: "I used to set up the riffs and the titles and the hook, and Mick would fill in. We didn’t think much or analyze. I’d go, ‘I met a fucking bitch in somewhere city.’ Take it away, Mick. Your job now. I’ve given you the riff, baby."

Drugs? Necessary. In the South, a black musician laid it out for Keith: "Smoke one of these, take one of these." Keith would move on beyond grass and Benzedrine to cocaine for the blast and focus, heroin for the two or three day work marathon. Engineers would give their all and fall asleep under the console, to be replaced by others. Keith would soldier on. "For many years," he says, "I slept, on average, twice a week."

With money and success, though, there’s suddenly time to think — in Keith’s case, about all the things about Mick that drove him nuts. His interest in Society. His egomania. His insecurity. And his promiscuity:

Mick never wanted me to talk to his women. They end up crying on my shoulder because they’ve found out that he has once again philandered. What am I gonna do? The tears that have been on this shoulder from Jerry Hall, from Bianca, from Marianne, Chrissie Shrimpton… They’ve ruined so many shirts of mine. And they ask me what to do! How the hell do I know? I don’t fuck him! I had Jerry Hall come to me one day with this note from some other chick that was written backwards — really good code, Mick! — "I’ll be your mistress forever." All you had to do was hold it up to a mirror to read it… And I’m in the most unlikely role of counselor, "Uncle Keith." It’s a side a lot of people don’t connect with me.

If only it could be so simple as a man and his guitar! But there are other people involved, in close association, with a lot at stake — and here comes the business story, the drug story, the power story. It’s funny and silly. And, after a while, sad. Mick breaks away from the Stones and makes a solo record: "It was like ‘Mein Kampf.’ Everybody had a copy but nobody listened to it." Mick gets grand. Keith’s lost in drugs. From l982 to 1989, the Stones don’t tour; from 1985 to 1989, they don’t go into the studio.

And now they are rich. Beyond rich. Every time they tour or license a song, their wealth mounts — Keith, by most estimates, is worth at least $250 million. It’s ironic, really, for by any creative analysis, the Stones were over after "Exile on Main Street." And yet, here they are, almost four decades later, capable of producing the most lucrative tour of any year.

Like so many things these days, music is about branding — and there’s no bigger brand than the Rolling Stones. Keith may slag his band mates; he’d never mock the Stones. Because the band is, if his version is accurate, really his triumph. Mick provided the flash, but in rock and roll, a great riff will always trump flash.

A great riff will also trump time. We love rock for many reasons, and not the smallest is the way it makes us feel young, as if everything’s possible and the road is clear ahead of us. And here is Keith Richards, who never grew up and is now so rich he’ll never have to.

His story slows as it approaches the present, and you start to wonder if this Peter Pan life can get to its end without real pain ahead. And you think, well, there’s another side to this — if Mick started writing tonight, he could have his book out before he’s 90. But mostly, you wish you could go back to the beginning of "Life" and start again.