Books |

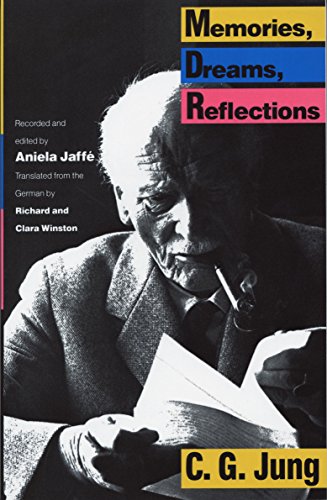

Carl Jung: Memories, Dreams, Reflections

By

Published: Dec 14, 2019

Category:

Memoir

Carl Jung’s writing is for the professional — it’s not particularly readable for the likes of me. But then there’s “Memories, Dreams, Reflections,” the book he wrote and dictated when he was in his 80s. Published in 1953, two years after his death, it’s the most interesting kind of memoir, offering more detail into his inner life than the events we’d expect to hear about. [To buy the paperback of “Memories, Dreams, Reflections” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Jung’s is a strange story. His parents slept apart. His mother was not quite right. His schoolmates “alienated” him — from himself: “I had the feeling that I was either outlawed or elect, accursed or blessed.” But a manikin carved on a ruler, sawed off and replaced in his pencil case along with a black stone from the Rhine, then buried under a floorboard in the attic — this restored his sense of identity.

Jung milked some illnesses until he’d convinced a doctor he had epilepsy. Then, when he was 12, he heard talk that he’d never have a normal life and be able to make a living. He made a dramatic improvement, fighting off fainting fits with a willful “Now you really must get to work.” And that, he writes, is “when I learned what a neurosis is.”

Still, he felt himself to be two people, simultaneously living in two periods. That split continued all his life — and, he believed, in everyone’s. The key point, for him, isn’t the dislocation but the sense that “something other than myself was involved ….as though a breath of the great world of stars and endless space had touched me or as if a spirit had invisibly entered the room — the spirit of one who had long been dead and yet was perpetually present in timelessness until far into the future.” (This does not lead him to traditional religion: “The farther away I was from church, the better I felt.”)

He made his way through medical school, emerging so poor that he made a gift box of cigars last a year. He had many ideas, but quickly learned that original ideas are best communicated by facts — and “I had nothing concrete in my hands.” But in his drive toward empiricism, magic got in the way. A wooden tabletop split for no reason. A knife inexplicably broke into pieces. “My old wound, the feeling of being an outsider and of alienating others, began to ache again.”

A very good BBC interview explores these ideas. For the really good stuff — the wisdom that might apply to you — go right to 26:00.

Inner experience is scary. Many people, Jung felt, run away. Too bad — he believed that much of the dissonance is created by society, and the victims are “optional” neurotics. Bridge the gap between ego and unconscious, and the suffering vanishes. Who has the most trouble doing this? Liars, of course. And intellectuals — “with them, one hand never knows what the other hand is doing.”

The beliefs Jung came to hold as an adult were, he felt, shaped by his childhood — not so much its events as the “fantasies and dreams” of his youth. This primacy of the unconscious is the great through line of the book. But Jung is also a sharp critic of the world. “Reforms by advances…are deceptive sweeteners of existence.” We pay for everything shiny and fast with a diminished quality of life. “Reforms by retrogressions” — by simplifying, by going back to customs long discarded — are, in the long run, cheaper and happier.

These words could have been written last week:

We rush impetuously into novelty, driven by a mounting sense of insufficiency, dissatisfaction, and restlessness. We no longer live on what we have, but on promises, no longer in the light of the present day, but in the darkness of the future, which, we expect, will at last bring the proper sunrise. We refuse to recognize that everything better is purchased at the price of something worse; that, for example, the hope of greater freedom is canceled out by increased enslavement to the state, not to speak of the terrible perils to which the most brilliant discoveries of science expose us.

In l944, Jung broke his foot and had a heart attack. On the verge of death, he saw the earth “bathed in a gloriously blue light” — a view from 1,000 miles into space. He sensed that “I had everything that I was, and that was everything.” And, most importantly, he grasped the urgency of affirming your own destiny, for in no other way can you develop an ego strong enough to stand up to the blows of life.

Jung provoked me to consider that my unconscious knows more than my mind does. He invited me to regard death as the way the soul achieves its missing half. When he writes that he can’t explain love, I found myself forgiving my own inability to define it. And I had to laugh when I confronted this simple truth: “People continued to exist when they had nothing more to say to me.”

Superficially, Jung and I — and you, perhaps — have little in common. To his death, he filled his pipe from his father’s tobacco jar. He built a tower. His interests included alchemy and UFOs.

And yet, for all his exploration, Jung was perhaps very much like us. Even at the end, he was a pinata of conflicting qualities: ”astonished, disappointed, pleased with myself …distressed, depressed, rapturous.” This cheered me up. It made me glad I’d waded — with some skimming — through a book that gave a layman a way of entry to a new thinking about the long view. And it reassured me, for I felt, as you may:

Ah, these good, efficient, healthy-minded people, they always remind me of those optimistic tadpoles who bask in a puddle in the sun, in the shallowest of waters, crowding together and amiably wriggling their tails, totally unaware that the next morning the puddle will have dried up and left them stranded.

In a word, Jung reminded me that courage belongs in the life kit of everyone who wants to be conscious. And that there’s no freedom quite like the one you have in your head.