Books |

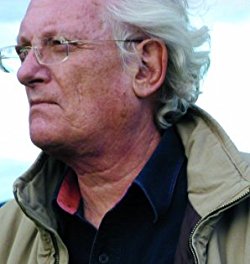

Peter Temple

By

Published: Jun 07, 2021

Category:

Fiction

Peter Temple died in 2018. His death was a loss to readers who like novels that seem to be about crime but are really about much more. And it was a very big loss to me, for although we never met — Peter lived in Australia, and didn’t travel — we were friends. Writer friends. Pen pal friends, starting when I praised one of his books. Unequal friends, really: He knew that I loved him, and Peter, being Peter, was gruffly affectionate in response, the way you are with a dog that’s barky and not fully trained.

Like this:

I’d write him: “Consider this, from Paul Simon: ‘When I’m making music, I’m no age.’ True for you?” And he’d reply: “How wonderful it must be to be always 14 in your mind.”

I urged him to read James Salter, another writer who couldn’t write a dead sentence. His response: “Changing your name to become a writer?” (Salter began life as James Horowitz.) But then he read Salter, and he saw what I did. His praise was self-denigrating: “Imprisoned by rain and wind, I spent the weekend remedying my ignorance of the works of James Salter. I should be so lucky as to be mentioned in his company. When you see him, please tell him some prick in Australia sends his admiration and his thanks.”

When I rewrote O.Henry’s Gift of the Magi, I sent it to him, calling it “a sad and complex story.” Peter would have none of that: “It certainly saddened me when I read it, aged about ten.” And then, having put me in my place, he explained the story to me as no one else could: “Many, many years later, when I’d read a few more books, my father, who is now recognizable to me as an agrarian socialist, said O.Henry meant the story to be an indictment of capitalism: all else sold, all you have left is your glossy hair, just like the women of Eastern Europe who still crop themselves.”

There was a long silence. I wrote him last month: “I’ve missed volleying with you. And as I see no new book from you on Amazon, I feel like a Jewish mother — concerned. Please hold up a finger and state your condition.”

I got no answer. Now I understand. He had cancer. He’d told no one. His death, at 71, was private. I’m sure his cremation was too. Dust to dust: Peter was tough that way.

Peter was, like Salter, a writer who needed little editing because he was a ruthless editor of his own prose. As his publisher noted in a tribute, “Editing him was like editing granite. He loathed it.” The publisher recalled an email he surely received more than once: “I have done all the corrections AND I DON’T WANT ANY MORE F..ING EDITING.”

It’s remarkable that Temple, born and raised, in South Africa, didn’t become a novelist until he was 50 and living in Australia. He won Australia’s Ned Kelly award five times for crime writing, the first for his debut novel, Bad Debts. In 2007 he won the British Crime Writers major award, the Gold Dagger, for The Broken Shore. And in 2010, he was the first crime writer to win the Miles Franklin award for his novel, “Truth.” His Jack Irish books, about a lawyer and alcoholic who becomes an investigator, were made into three television series starring Guy Pearce.

Why crime? “What is more at the heart of social life than the crime against the person? I see it as an excuse for beginning the narrative. It has its own logic and relentless drive. It is a reason for things to happen and for the way characters behave.” He knew it was considered a lesser genre, and said as much in his acceptance speech for the Miles Franklin award: “I’ll thank the judges anyway. They’ll have to take the flack for giving the Miles Franklin to a crime writer, and all I can say, my advice to them, is cop it sweet. You’ve done the crime, you do the time.”

A noted writer said of him, “Peter Temple was to terse blokes with hard jobs and wounded souls what Proust was to memory. He made every sentence count and shot the stragglers.”

Here’s what I’d say: “I thank God that Peter lived 10,500 miles from New York and wasn’t widely read by the New York literary snootballs who occasionally like my writing, because whatever is chiseled and tight in my fiction is largely copped from him — a crime that would, I think, make him smile.”

These are his books. If you read one, you’ll read more. And you’ll stay up late.

Here’s the start of my review of Identity Theory, the first book of his I read:

Johannesburg, 2 PM on a weekday. Here is Niemand, no first name. He’s working out. Inside. “Outdoors had become trouble, like being attacked by three men, one with a nail-studded piece of wood.” Niemand is no victim: “The trouble had cut both ways: several of his attackers he had kissed off quickly.”

Niemand, we are told, “didn’t get any pleasure in killing.” Which hasn’t stopped him — Peter Temple takes a page to recount three killings on his scorecard. You’ll have no problem agreeing with Niemand’s actions.

Now we’re on page three. An aging Mercedes — actually, a new one, hidden under an old, rusting, dented body — picks Niemand up. We meet Mkane, his partner. They’re on personal protection work today, collecting a woman at a shopping center and making sure she gets safely home.

She does. Niemand and Mkane check the house out. Thoroughly: “There was one vehicle in the garage, a black Jeep four-wheel-drive. A camera at floor level showed no one hiding beneath it.” Rather extreme precautions, you think. What kind of world is this that requires “every cupboard, every wardrobe” to be checked?

The woman drinks champagne. Niemand “holstered his pistol, didn’t feel relaxed.” Her husband arrives, scorning Niemand’s black partner. Niemand looked up, “saw something on the ceiling behind him, something at the edge of his vision, a dark line not there before….The man in the ceiling pushed open the inspection hatch…”

Carnage. Out of nowhere. With hot blood and screaming and guns that don’t work and then do, and bodies, bodies everywhere. In the silence that follows, Niemand inspects the husband’s briefcase: envelopes, papers, a video cassette. The phone rings. He answers. The papers? The tape? Yes, Niemand has them. Will he bring them out? Yes, but how much? “Twenty thousand. And expenses.” And he’s off to London…

And so ends chapter one. Take a breath. Your first in a while. Turn the page.

Here’s the start of my piece about The Broken Shore.

The book starts small. Joe Cashin, a police detective currently assigned to a small town near Melbourne, responds to a widow’s distress call. Her trouble suggests the scale of local malfeasance — someone’s in her shed.

Cashin apprehends the man, inspects his clearly bogus decade-old identification.

Could be a murderer, the widow suggests. Killer. Dangerous killer.

It’s a small moment, but let’s appreciate the accuracy. That is, the widow’s reaction. The way she talks. And Cashin’s reaction: He drives the man to a bigger road.

And then this, watching the man walk away, “swag horizontal across his back, sticking out. In the morning mist, he was a stubby-armed cross walking.”

And here’s a moment from Truth, his last and best novel:

Laurie doesn’t see him, so Steve Villani is able to study his wife as she walks toward him.

Jeans, black leather jacket, thinner, different haircut, a more confident stride.

He hasn’t planned it, but he can’t help himself. “You’re having an affair.”

She says this isn’t the place to talk. He won’t let it go.

“Fuck meeting with the boyfriend, is that it?”

“I’m not having an affair,” she says. “I’m in love with someone, I’ll move out today.”

Not a word wasted, every beat true, drama at the red line, a surprise that packs a wallop. Compared to most thriller/crime writers, Peter Temple was Dostoevsky. I raise a glass to his memory.

—-

A TRIBUTE FROM HIS PUBLISHER, MICHAEL HEYWARD

In 1996, when he was about to turn 50, Peter Temple published “Bad Debts,” his first novel. He had by then lived in Australia for 1½ decades, after leaving his native South Africa at the height of apartheid.

He had worked in journalism and academe in Sydney, Bathurst and Melbourne. In 1989, with his wife Anita Rose-Innes and their son Nicholas, he decamped to Ballarat, 90 minutes west of Melbourne, and there he stayed, inevitably with a poodle or two at his feet. He was a late starter. Could he write fiction worth the candle? He had spent just a few years in Melbourne. Could he bring it to life in a novel?

Here is the opening page of Bad Debts. It’s the first time we hear the voice of Jack Irish:

I found Edward Dollery, age forty-seven, defrocked accountant, big spender and dishonest person, living in a house rented in the name of Carol Pick. It was in a new brick-veneer suburb built on cow pasture east of the city, one of those strangely silent developments where the average age is twelve and you can feel the pressure of the mortgages on your skin.

Eddie Dollery’s skin wasn’t looking good. He’d cut himself several times shaving and each nick was wearing a little red-centred rosette of toilet paper. The rest of Eddie, short, bloated, was wearing yesterday’s superfine cotton business shirt, striped, and scarlet pyjama pants, silk. The overall effect was not fetching.

“Yes?” he said in the clipped tone of a man interrupted while on the line to Tokyo or Zurich or Milan. He had both hands behind his back, apparently holding up his pants.

“Marinara, right?” I said, pointing to a small piece of hardened food attached to the pocket of his shirt.

Eddie Dollery looked at my finger, and he looked in my eyes, and he knew. A small greyish probe of tongue came out to inspect his upper lip, disapproved and withdrew.

A reader might grow old hunting about for the equal of that final paragraph. All of Temple’s books are studded with diamonds cut like this. He wrote spare, audacious sentences that give shape to emotion, like poor Eddie Dollery’s fear, for which we hardly know whether to feel compassion or contempt. Pain, grief and melancholy stalk the streets of Temple’s fiction, but there isn’t a page without sly humour or where the language doesn’t gleam. His heroes — Jack Irish or Joe Cashin from The Broken Shore, damaged men, whom life has beaten to a pulp — never lose their dry wit.

When Jack Irish isn’t part of a scam at the track or planing aged walnut boards in Charlie Taub’s workshop, he listens to Mahler and breakfasts on anchovy toast, drinking tea from bone china. Some of Temple’s female readers discreetly inquired how it might be arranged for them to sleep with Jack Irish.

“The Broken Shore” and “Truth” were the last novels he published. When he delivered the manuscript of “The Broken Shore” in 2005, we knew we had something special. It made him famous and brought him the audience he deserved. It sold more than 100,000 copies in Australia and was published in more than 20 countries. It gave him the honour of being the first Australian to win Britain’s Gold Dagger, the hall of fame for the world’s greatest crime writers.

“Truth” was darker and sadder, a long masterly bass note about the futility of things. It won the Miles Franklin Award in 2010, the first crime novel to be awarded Australia’s most prestigious literary prize. Peter was astonished. He had already sent me a form guide describing each of the contenders as if they were horses at the barrier. He rated his own chances at 200/1: “Ancient country harness racer attempting new career. Should be a rule against this. No.”

He was the harshest critic of his writing. He loved complex plots and tortured himself trying to wrestle them into submission. “The f..king thing has about 15 strands,” he wrote to me about Truth. “I am like those Telstra men you see in holes by the roadside, except they look happy and they know what to do.” Editing him was like editing granite. He loathed it: “I have done all the corrections AND I DON’T WANT ANY MORE F..KING EDITING.”

He was curious and sceptical about everything. He gave the impression that he had networks of informers all over the place providing him with the inside story, an attribute he shared with Jack Irish. He had read everything. He was proud, shy, outrageously funny, a charismatic curmudgeon. He loved pushing relationships to their limits. “Michael: Are we breaking bread on Monday night or would you rather break my neck? Yours, Peter.” He could be disarmingly generous and completely ruthless. He often conducted contractual negotiations under the alias of Agent Orange, a fop and a snob with a nose for cash and overpriced alcohol: “If you are staying at Claridge’s, do join me for a beaker of Bollinger. If you aren’t, don’t.” It was impossible to be bored in his presence.

Peter could parse a sentence and a society. His poet’s ear gave us dialogue that is a brutal celebration of the way we speak. He heard us and saw us, our lies, our loves, our corruption and our kindness. He wrote about Melbourne from the inside out: its football, racetracks and shonky property developers. His novels will be required reading for historians of the city.

Writers are sometimes plainer than their books, but Peter’s conversation could light up a room. We will never hear his laughter again, or see that half-secret smile, and the world is a lesser place. It is a formidable achievement to write a novel that can stay in print for a decade. Peter wrote nine in 13 years. Each one got better.

They will outlast us. Farewell, Temple.