Books |

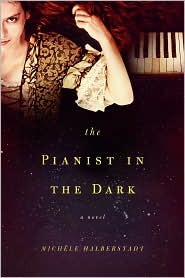

The Pianist in the Dark

Michèle Halberstadt

By

Published: May 22, 2018

Category:

Fiction

Sheku Kanneh-Mason played three pieces at the Royal Wedding. One was by Gabriel Fauré. One was by Franz Schubert. The third was “Sicilienne,” by Maria Theresia von Paradis. If you saw the program, did you shake your head at that last name? As it happens, a fine novel tells her story. And it’s quite a story…

“The Pianist in the Dark” confirms my prejudice in favor of short books. It starts like this:

She doesn’t know the color of the sky or the shape of the clouds, doesn’t know the meaning of blue or red, of dark or pale. She lives in blackness.

Thirty words, and we’re in the world of a blind girl. We’ll quickly learn that she’s not just any blind girl — she’s Maria-Theresia von Paradis, she lives in Vienna, and she is the only child of the Imperial Secretary to the Empress. So far, so true: There really was a woman named Maria-Theresia Paradis. She lived from 1759 to 1824, she was blind, was taken up by the Empress, Mozart did or didn’t write a piece for her.

Maria-Theresia played piano before, around age 3, she went blind. She was said to have been a child prodigy; at 17, she was a virtuoso, and the Empress gave her an annuity of 200 ducats. But her genius at the keyboard was eclipsed by the mystery that surrounded her. Something made her go blind overnight — what was it?

In this novel, which sticks close to the facts for much of the book, she knows why she’s blind. But she won’t say. Her reason:

She felt that being blind was the only power she had over them [her parents]. She was the object of their obsession, the subject of their confrontations, but without her, her blindness, they would have nothing to discuss. Her handicap freed her from her parents and at the same time enabled the three of them to remain a family.

Most of us fear blindness, hope it won’t happen to us. Not Maria-Theresia:

She is no longer frustrated to have lost a sense, the appeal of which she has forgotten. What is sight, exactly? To know what everyday objects look like? A table, a chair, a mirror? But she knows [what they look like] better than anyone, in her own way, and this way suits he… With time, she has persuaded herself that sight is an illusion that leads the other senses astray, renders them ineffective. Whereas hers are always alert.

Her blindness leads her to Franz Anton Mesmer, low-born and ambitious, married to a rich woman, a friend of Mozart. He gives a concert on an instrument of glass bowls filled with water. Marie-Theresia attends. They meet. It turns out that he has had some success as a healer. He has a theory of animal magnetism.

“Mesmerism” is named for him. He could “mesmerize” people. He volunteers his services to Maria-Theresia. And mesmerizes her.

Ah. A story of music. Of privilege. Of love. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

What can Mesmer offer a young, beautiful, virginal, talented blind woman? Sight? Acceptance as a woman? Love? A clear understanding of the way the world works?

All of the above. But what you’ll notice most is the love story, which is the book’s only weakness. Consider:

Maria Theresia was unaware of Franz Anton Mesmer’s medical ambitions. All she knew about him was his reputation as a patron of the arts. She had heard him play with orchestras and remembered him as being a mediocre pianist.

But that evening, sitting between her parents on the bandstand near the gazebo at the left side of the garden, she could only admire the quality of his improvisations on the glass-harmonica.

Was the instrument responsible for the trembling sonority, or was it his way of playing it? A sense of peace emanated from that assembly of air, glass, and water.

Maria Theresia lifted her head, offering her senses a well-deserved pause. She lost the panicky stiffness she felt when surrounded by strangers whose gazes seemed to pierce through her. She no longer felt weighted down by the baubles that encumbered her neck and earlobes. She felt dizzy, as if a wind had risen and blown right through her. Her hands were quivering as they did sometimes at church when prayers overlapped, as if they were taking a shortcut to heaven.

The concert was over, but she was shaking too much to applaud.

She asked her parents to bring her some cold water.

Her temples were moist. She was shivering.

“I was hoping you might take comfort in the music.”

She sensed a figure leaning over.

There’s not much of that. Think of her talent: She played Handel fugues to George III. She wrote five operas, various cantatas, lieder, and numerous piano works. Was she afflicted? Not in this novel. And not in her life.

BONUS VIDEO

One of her compositions is cherished. If, that is, she was really the composer.

These are not small questions. Here, they are answered swiftly, dramatically, memorably. And in the hour it takes for you to be entertained, you can also be enlightened – there really was a woman named Maria-Theresia Paradis. She lived from 1759 to 1824, she was blind, was taken up by the Empress, did know Mozart, did take a cure with Mesmer. In her later years, she was known as a composer.