Books |

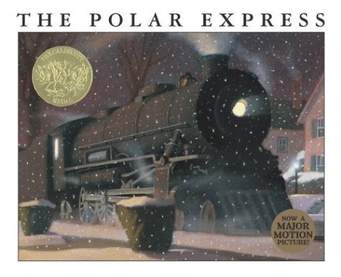

The Polar Express

Chris Van Allsburg

By

Published: Dec 01, 2015

Category:

Children

What is the most interactive medium of all?

A rich, wise man in Silicon Valley — so rich he did not need to offer up the kneejerk response: “online media” — had the right answer:

A person in a chair, reading a book.

I instinctively knew that was right. As, surely, do you. For we have all had that magic experience of opening a book and entering a drama of knights and knaves, princes and goddesses. This world? We’ve left it. We are living the book.

I would go one step further: The most interactive medium of all is a person in a chair, reading a book to a child.

Especially this book.

On Christmas Eve, a father tells his son that there’s no Santa Claus. Later that night, a train packed with children stops in front of the boy’s house. He hops on and travels to the North Pole, where Santa offers him the first toy of Christmas. The boy chooses a reindeer’s bell. On the way home, he loses it. How he finds it and what that means — that’s where you reach for the Kleenex.

A simple story. A timeless story, and on purpose — as Van Allsburg has said, “If you opened up my books and there was no copyright page, you wouldn’t be able to tell exactly when it was published.” It’s precisely because the illustrations do not anchor us to our time, our town, that we can deal more directly with the theme of the book. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here.]

That theme is belief. Not in Santa, though that will do just fine for kids. Belief in really big things, things we hope are true even in the face of all the information that says they are not. Again, Van Allsburg: “We can believe that extraordinary things can happen. We can believe fantastic things that might happen. Or we can believe that what we see is what we get. But if all that I believe in is what I can see, then the world is a smaller, less interesting place.”

Most of the time I believe in magic. Sometimes I believe in miracles. That is the baseline of all the greatest spiritual stories — the impossible happens. And you can’t explain it. Except, perhaps, as C.S. Lewis does: “Miracles only occur to people who believe in them.”

So as your holiday gift to yourself, buy the book. Not the "special edition” with the bell and the CD and Lord knows what else. Not the Kindle download. The basic book. Because it’s all you need.

And then, of course, find a child. And settle in your chair. And start to read. Before you know it, your eyes will mist, you’ll be reaching for the Kleenex, and — and this is the best part of all, especially for the sophisticated and the hard of heart and the bitterly disappointed — you will believe.

Note: There’s also an animated movie, narrated by Tom Hanks. It’s good. But really… you want to read the book to a child. For the kid. And for you.

—–

A NOTE FROM CHRIS VAN ALLSBURG

Over the past twenty-five years, many people have shared stories with me about the effect that reading “The Polar Express” has had on their families and on their celebration of Christmas.

One of the most poignant was told to me five or six years ago at a book signing in the Midwest, on a snowy December evening. As I inscribed a book to a woman in her sixties, she told me that it was the second copy she had owned, and wanted to know if she could she tell me what had happened to the first. “Of course,” I answered.

A dozen years earlier the woman, who had no children of her own, befriended a neighbor, a boy of about seven, named Eddie. He would often cross his driveway to visit her.

She had a collection of picture books, which she read to him, but around the holidays, the only story he ever wanted to hear, over and over, was “The Polar Express.” One year she offered to give him the book, but Eddie declined because he wanted to hear her read it aloud to him, which she continued to do every year until the boy and his family moved away.

Years later the woman learned from a mutual acquaintance that Eddie had grown up and become a soldier. He was stationed in Iraq. Since Christmas was approaching, the woman decided to send him a gift box. She included candy, cookies, socks, and her old copy of “The Polar Express.” She wasn’t sure what a nineteen-year-old battle-weary soldier would do with the book in an army barracks in the Middle East, but she wanted him to have it. A month later, after the holidays had passed, she received a letter from Eddie.

He told her he was very happy to have heard from her and to get the box of gifts. He had opened it in his barracks, just before curfew, with some of his fellow GIs already in their bunks. A soldier in the next bunk spotted the book. He knew it well from his own childhood and asked Eddie to read it. “Out loud?” he asked. “Yeah,” his buddy told him.

Eddie, quietly and a little self-consciously, read “The Polar Express.” When he’d finished and closed the book, a moment of silence passed. Then from behind him a voice called out, “Read it again,” and another joined in, “Yeah, read it again,” and a third added, “This time, louder.” So Eddie did.

He wrote to the woman that he’d stood up and read it to his comrades just the way he remembered she had read it to him.