Books |

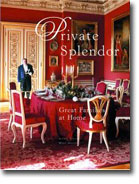

Private Splendor: Great Families at Home

Alexis Gregory

By

Published: Jan 01, 2007

Category:

Art and Photography

On the occasion of my first dinner with the woman who would become my first wife, a man answered the door. He wore a crisply tailored dark suit. I shook his hand. Alas, he was the butler.

Later, this woman laughed about my faux pas. Because it didn’t speak to a lack of class. It really was funny — butlers went extinct in these parts in 1944, when the draft took them away to fight in World war II.

Butlers have not gone extinct at the eight palaces Alexis Gregory explores in this remarkable book of historical essays and double-page photographs. But they aren’t usually on the permanent staff, as they were in the not-so-long-ago days when Prince Johannes von Thurn und Taxis had 200 on the payroll, ten of them footmen. (The Prince was a special case — his family founded and owned the German post office, and when the government confiscated it, the Thurn und Taxis were given the castle as a consolation prize.)

Many of these houses are now open to the public. Some have been carved into apartments; with luck and connections and a sturdy checkbook, you could live in one. But not in the rooms photographed here. These rooms are for the occasional tour. These rooms are for private parties. But these rooms are not, in the main, for photographic display.

Alexis Gregory, friend to their owners, has infinite patience for the seemingly boring historical details of these houses. A hundred, two hundred, three hundred years ago — he understands that stories which might seem unimportant to us are crucial to the continuity of ownership. Because that’s the thing about the great fortunes of Europe — they last. For hundreds of years.

In America? We’re lucky to see wealth extend into the third generation. Why? Tucked away in an afterword, Gregory offers a terse explanation: ancestor worship among the European nobility. “Palace building,” he writes, “is the most fundamental expression of power.” I guess Americans just don’t worship their ancestors. Or maybe it’s that we’re a little too preoccupied worshipping ourselves. Whatever. At a certain level, it’s better to abandon Deep Thoughts and just revel in the great stories and the kind of photography that insiders sometimes call “house porn”.

Start with Kasteel de Haar, the largest castle in Holland. Built in 1162, it was headed downhill as the last century began. Then its owner, Baron Etienne van Zuylen, married Helene de Rothschild, of those Rothschilds. Soon after the marriage, he told her of his dream: to restore the house. And it became so.

In Seville, we visit the Casa de Pilatos, built in a dazzling combination of Gothic, Muslim and Renaissance styles. On to Harewood house, in Great Britain, where, after World War I, Henry Viscount Lascelles had a problem — unlike his ancestors, he really couldn’t marry a German. His solution was to marry Princess Mary, only daughter of George V, restore the house and become a major figure in theatre and opera.

At Chateau de Harque, in eastern Lorraine, Princess Minnie de Beauveau Craon greets Alexis Gregory in sensible tweeds and installs him in a guest room with “an elegantly faded spread and slightly shiny pillows.” Not an embarrassment in these circles. Her butler Lucien was in service to Basil and Elise Goulandris. Her uncle was Don Simon Patino, known as the “tin king” because the Bolivian once controlled the world’s supply; still, the family had to sell 5,000 acres of land near Paris to pay for a new roof and fix the facade. (Grieve not. This Princess has it a great deal better than a previous chatelaine, who had an “irascible husband and a few very prominent lovers to make her life more agreeable.”) In Palermo, we tour the Palazzo Ganghi, home to the ballroom used in Visconti’s “The Leopard”. And the Roman palace is, as you may expect, just across the Tiber from the Vatican.

On the story side, it’s hard not to favor Bavaria’s Schloss St. Emmeram, “the largest private home in Europe still maintained by a single family.” Prince Johannes von Thurn und Taxis — “a playboy of the western world…marriage was not high on his list of priorities” — came to his senses when he realized that “a fortune estimated at three billion dollars was hanging in the balance.” Marriage and children followed. And, after his death, the almost inevitable news of financial mismanagement. In the fire sale that followed, the widow’s tiara was acquired by the Louvre.

Gregory would have us believe that these “exalted piles” were merely stage sets for elegance and wit:

High standards of conversation are one of the staples of chateau life in France, and those who cannot keep up are not asked back. You must have at your fingertips the latest political and social gossip, must have read the most interesting new books, seen the best exhibitions, have strong and original opinions, and been to the most controversial opera productions in Aix, Salzburg, or at the Bastille. A friendly, American-style “What are you busy with now?” simply won’t do, and arrival in a brilliant salon, such as that of Haroue, can cause the sort of butterflies in your tummy that you last remembered when taking a college exam.

Butterflies? This is the sort of exam I was born to pass. You too, I’d bet. And I know we’d all look good in paneled rooms with claret velvet curtains and fireplaces with carved white marble scenes of the Garden of Eden. Sadly, my invitation seems to have been lost in the mail. If this is your situation — or if you have a friend who pines for standards of hospitality that ended a century ago — here’s a book that will give your coffee table some welcome dignity.

To buy “Private Splendor” from Amazon.com, click here.