Books |

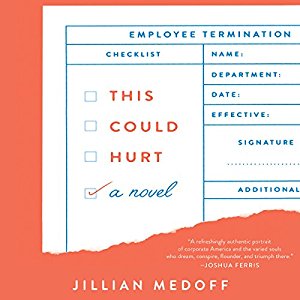

THIS COULD HURT

Jillian Medoff

By

Published: Feb 07, 2018

Category:

Fiction

Ursula Le Guin had contempt for most modern novels, which she described as “fiction about dysfunctional urban middle-class people written in the present tense.” Me too. Every week I get a pile of books by noted writers, and every month I give a large bag of books away. Why? They’re all “bubble books” — written about white people who live in one of 20 American zip codes. Their problems and situations are just too narrow for me. I crave a book that’s well written enough for critical praise but broadly appealing enough to be sold in airports. That’s what Jillian Medoff has done in THIS COULD HURT, a novel about people who work in Human Resources in a company that’s stocked with recognizable humans. Someone’s aging and sick. Someone slacks. Someone is inappropriately sexual. You‘ll laugh, you’ll cry, but mostly, you’ll nod your head in relief — at last, a book you can read.

So here we are at the Ellery Consumer Research Group. It’s 2009. The economic meltdown was last year —the Human Resources department lost almost half its employees — and now the CEO wants Rosa Guerrerro, Chief of HR, to cut more. She’s already made one cut — a trusted lieutenant, who embezzled. Who’s next? Lazy training and recruiting director Rob Hirsch? Too cool for HR Wharton grad Kenny Verville? And then there are the stalwarts, who cover Rosa after she has a minor stroke. Because this is a book about work, there are org charts and footnotes — thank God, no Power Points – and a clever epilogue. “Mad Men?” This is the exact opposite — if you work in an office, these are people you know. And laugh with, and at. And weep for. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Jillian Medoff knows this world like the birthdays of her children. [Proof: I Refuse to Be the Office Mom. Subtitle: “I am too fucking busy to be the in-house cop.”] So it seemed like a good idea to ask her to bring us into her world.

JK: Your book is so acutely observed it seems almost reported. Tell me the background.

JM: I’ve had a long career as a management consultant, advising Human Resources executives on how to communicate with employees during organizational changes that range from high-stress events (i.e., mergers & acquisitions) to smaller but equally complicated benefit updates (i.e., implementing a 401(k) plan). I’ve worked for several Fortune 500 companies (Deloitte, Aon, Segal), so I have a comprehensive understanding of HR, but mostly from the outside looking in.

In 2009, I was laid off from Aon after 10 years and took a job in the HR department of a research company. My boss, a woman in her sixties, was a bully who lied, yelled, and tormented her staff; she also appeared to be losing her faculties. She told me she’d had a stroke a few years before, and I wondered if this accounted for her erratic behavior. She had a small staff of senior managers who had worked with her for many years and were very loyal, despite fearing her wrath. (The company had gone through several rounds of layoffs, so her team probably thought that by saving her, they’d also save themselves. Unfortunately, business doesn’t always work that way.) They covered for her in meetings and behind the scenes in ways that surprised me. I eventually left the company (it’s impossible to work for a monster, no matter how much you may sympathize) but her story—and her staff’s—haunted me.

In 2010, I was back in consulting but now I was older and suddenly aware of my age. Corporate life is hard on aging women, and I kept thinking about my former boss. I had so many questions, which is how I usually approach a new novel: it’s a way to get answers to all my unanswerable questions. I knew very little about her personal life—or the personal lives of my colleagues—despite having worked together all day, all week, for a year. This interested me too; how we spend so many hours with coworkers, and yet there’s so much we don’t know about them; we know what they want us to know. I’d always wanted to write about corporate life, and my former boss’s stroke offered a way in. I imagined what I’d do if my own boss suffered a medical emergency: Would I visit her in the hospital? Bring flowers? Hug her? How long do I stay? Do I sit down? As a novelist, I’m focused on the thin line between tragedy and comedy, in the place where they blend into each other; where, if you’re not laughing, you’re broken. I find that sweet spot, and then I’m off.

JK: Because of recent sexual harassment stories, we think of HR as the spineless stooge of management. Is it?

JM: In business, information is leverage and secrets are currency. People have long associated HR with clerical duties (filing forms), employee morale (Hat Day) and bad news (we’re sorry your services are no longer needed here). HR, however, has so much information about employees that it really is the most powerful, most underestimated and misunderstood department in an organization.

Created during the height of unionization as a way to advocate for employees, HR is now a strategic partner to the business. This means aligning HR’s goals with the goals of the organization: increase revenue, reduce overhead, and stay out of court. So the HR department’s loyalties are divided, with HR staffers’ loyalties divided even further.

This shift is best illustrated in the recent sexual harassment revelations and rise of the #MeToo movement. A lot of people are wondering why, if HR knew about Weinstein, Ailes, etc., they didn’t take steps to protect their employees. But in fact steps were taken—accusations, confessions, settlements. They ask: why didn’t HR protect their employees? The better question: which employees were they protecting?

JK: I only had one office job, and the boss there believed “If they’re not screaming, they’re not working.” So I’m stunned by the office culture at Ellery. Kenny has an MBA from Wharton and thinks he’s too good for his job. Rob comes to work but doesn’t do his job. This happens?

JM: Oh my God, you have no idea! Although I’ve had a few bosses who love to micromanage, the greater majority doesn’t, so as a senior manager, I’ve been largely independent—and so have my coworkers. I’ve worked at organizations after a downturn and subsequent acquisition, and during those months there’s a sense that anything can happen. Projects are started then abandoned, meetings are set up then cancelled. So yeah, like lots of employees, Rob and Kenny exploit the holes.

JK: This is the first novel with footnotes I devoured. From a footnote: “Everyone complains about men’s underhanded, backdoor business deals. But you know what? Women are worse.” Discuss.

JM: In my experience —allow me to repeat this b/c people love to point out all the ways I’m wrong: in my own unique personal experience and quite possibly no one else’s —I’ve worked for women who thrive under pressure, meet all their deadlines and are great project managers, but cannot look you in the eye and say “you’re screwing up.” Instead, they overcompensate with praise, talk behind your back and act passive-aggressively, simply to avoid dealing with the issue directly. It’s very unsettling; not knowing where you stand in a corporate job is crippling b/c much of your performance is based on perception. In this way, some women can be more difficult to work for than men because they’re less transparent.

JK: In her career, Rosa has learned one lesson: “Profits were imperative, people were expendable.” Have you witnessed any exceptions?

JM: Here’s a large moment: On 9/11, I worked for Aon, but my office was up on 59th/Lex not in the South Tower. We lost several colleagues that day, and Aon’s response was glorious: financial and emotional support, not just for the surviving family members but also for surviving employees, then a one-year memorial, plaques, pageantry—the works. And Jesus — the stories of how coworkers—ordinary people—helped each other find safety and shelter, both inside those buildings and on the ground; those stories are just heroic and beautiful. Flash-forward just a few years later, and Aon was laying off people right and left (sorry, right-sizing). I was shocked, although I shouldn’t have been—guess Pat Ryan (former CEO) didn’t really mean it when he said we were all part of the Aon family; rather, sometimes families sadly break apart.

Here’s a small moment: the other day, a colleague dropped his sandwich on the way to the kitchen; it literally fell out of his hand and plopped on the floor. Another colleague saw the sandwich fall, reached into his lunch bag, took out his sandwich and offered the guy half. Didn’t even think twice.

See? We’re a work family, sometimes the emphasis is on work, other times it’s on family.

JKK: Look at this put-down of millennials. Is it justified?

JM: Yes and no. In THIS COULD HURT, I have a few millennial characters, and made a point of showing a range of behavior, from “me, me, me” to “me, me, and a little bit of you,” to “you, you, and a little bit of me.” One thing I’ve definitely noticed is that the millennials in my office are far more confident and outspoken than I ever was. I appreciate this a great deal; I also encourage it. On the other hand (and there’s more than one hand), I see a lot of hubris too as well as the misguided belief that they can do anything and everything without training.

JK: With few exceptions, these are damaged, flawed people. Is that true of most/all offices?

JM: This is true of the whole world..

JK: Have the models for these characters read the book? If so, their reaction?

JM: I have no idea what you’re talking about. THIS COULD HURT is a work of fiction, and resemblance to anyone, living or dead, is purely coincidental..

JK: You have kids. Do you hope they won’t work in offices?

JM: I hope they work. That’s all I want, for them to be able to support themselves so I can die without worry.

JK: Why are you still working so hard at a corporate job when you’re clearly happier writing novels?

JM: Excellent question! I wrote an essay about this.