Books |

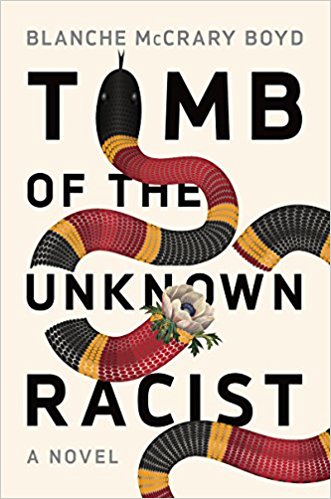

Tomb of the Unknown Racist: A Novel

Blanche McCrary Boyd

By

Published: May 08, 2018

Category:

Fiction

I had the pleasure of reading “Tomb of the Unknown Racist” in manuscript, but I really knew nothing about Blanche McCrary Boyd. I hadn’t read any of her other novels; I knew her writing only from a few essays, in forever ago 1982, in the ironically titled “The Redneck Way of Knowledge.” I didn’t know she’s Roman and Tatiana Weller Professor of English and Writer-in-Residence at Connecticut College. I had no idea of her badass life history. No idea of the scope of her imagination, which is so wide-ranging that reviewers describe her novels as “unclassifiable.” And no idea that “Tomb of the Unknown Racist” — her first novel in 20 years — would be so personal, political and original until she alerted me: “Writing about racism as a white person is a tricky business because, like all white people, it can be difficult for me to see how my own embedded racism might affect my work… That’s only one of my concerns… In any case, it’s probably a book with something to offend everyone….”

And with that warning, I was pre-hooked.

Here’s how “Tomb of the Unknown Racist” starts:

One spring evening in the year 1999 my mother and I were watching Wheel of Fortune, our matching rocker-recliners locked into their forward positions so we could reach our fast food burgers and fries, when a news bulletin interrupted the show: two young children had been kidnapped from a Native American reservation in New Mexico. The announcement was brief but Wheel of Fortune switched straight to commercial, and Momma had already guessed the puzzle: surrender to win. Dark, shiny smudges marked her hamburger bun since she had painted blue eye shadow on her lips that morning. On the days I took care of her, I let her do whatever she wanted.

Later that evening, after I had arranged her in the great canopied bed with the white George Washington spread (she was wearing a cotton nightgown embossed with an image of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer) she whispered, “It was the S and the double R combination that gave it away.”

“So how did you know the first word wasn’t serrated?” Serrated had been my own guess.

Her dark eyes gleamed up at me, deep in their orbits. “Don’t be silly, honey. That word only has two Rs, and there aren’t enough letters.” She called me honey whenever she couldn’t remember my name.

Her hair was encased in a pair of white nylon underpants to preserve its shape. I had removed all of her makeup, including the lipstick on one eyelid. Either she had stopped with one eye because she sensed something was wrong or she simply got distracted.

Leaning back against her wedge of puffy pillows, she stared past me through the balcony’s closed glass doors toward the lights of the Cooper River Bridge, glittering in the distance. Still fully clothed, I kicked off my hiking boots and settled on top of the covers on the other side of her bed so we could watch the 11 o’clock news together.

The kidnapping in New Mexico was the lead story. A brief video revealed a teary young woman identified as Ruby Redstone emerging through the doors of a hospital Emergency Room. She wore an ankle-length mauve skirt and a white blouse splashed with dried blood, almost like a matching decoration. Her straight black hair was pulled back, and a lemon-sized patch of scalp above her forehead had been shaved and bandaged. She leaned intensely toward the camera. “I beg of you, whoever you are, let my children go unharmed!” She was riveting, although my view may have been altered by recognition. Despite her auburn skin, Asiatic eyes, and different last name, I knew immediately who she was.

“Momma,” I whispered, “that’s our Ruby, all grown up.”

“Tomb of the Unknown Racist” is the third volume in a trilogy. No need to go back and read the first two. All you need to know about Ellen Burns is that she’s a one-woman mismatch, the kind of freak — drug addict, alcoholic, sexual glutton — only God loves unconditionally. Now she’s sober. But not exactly housebroken. Soon after that newscast, this “aging lesbian outlaw” is on a mystery tour, which turns out to be much more than a missing persons quest. [To read the rest of Chapter 1, click here. To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Ellen’s questions start with her brother Royce Burns, the celebrated novelist who became the kind of batshit crazy white supremacist who joins a terrorist gang and is, predictably, killed by government agents. Or did he die? Was it really Royce in that coffin? What’s with Ruby? Where are her children? Is it possible that Royce isn’t really dead? What if he kidnapped them?

Many of your favorite mystery/thriller novelists could write a strong plot starring a version of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber. Few can write as well as they plot. Boyd does. This is a partly a function of her skills as a teacher — her students’ assessments credit her with a legendary capacity to listen closely, read their work with the same attention she gives to her own writing, and then deliver surgical commentary. But that no-bullshit objectivity isn’t some literary choice. It comes from surviving a life that would have put most of us in a rocking chair, brain dead, before we were 40.

This interview tells her story at length. Here’s the capsule version: raised in South Carolina by a family of “overt racists,” Boyd lasted one semester at Duke. “I was drunk all the time, and a trouble maker. I used to hypnotize people. I told the Dean I was going to quit school and get married and she said, ‘good.’ I married a man who wouldn’t put up with my drinking. He didn’t even let me have a television. He told me to get serious, get a job and get my life together. I had never been able to listen to anyone before. He was a smart, stable, nice man and we loved each other.”

She graduated from Pomona College with a hat trick — high honors, Phi Beta Kappa, a writing grant to Stanford. That led to a Vermont commune that struck every cliched note for revolution. “That anyone thought something was going to happen in this backwater state was absurd,” she says. “I only stayed there for about a year and a half. I did a lot of drugs and eventually got arrested.”

New York came next, a grotty apartment with a typewriter for furniture. She wrote a novel. “My drinking and drugging kind of leveled out. It was like being on an escalator that only went down. I thought the solution was to write another novel. I did but it wasn’t any different. Then I accidentally became a rock and roll critic, which was hysterical.”

Back in South Carolina, Boyd joined a crew of rich drug users. In 1980, when one of them shot herself with a shotgun, Boyd was in the room: “I saw it happen. There were pieces of her body on the wall, and she was conscious. It was horrible. It was one of those moments where you know your life has changed but you don’t know how, and I realized that she was more honest than me. We weren’t cool; we were dying and I didn’t know who I was or what I was doing. I think sanity is a really fragile thing, and that drugs and alcohol become easily abused.”

Quitting alcohol was hard. Quitting drugs was harder. But on May 19, 1981, Boyd was clean. Two weeks later, she was interviewed by Connecticut College for a one-semester teaching job; it has lasted for 36 years. She wrote and her byline became familiar; readers started looking forward to her pieces. “I was astounded,” she says. “I tell my students that if I’m a person in a position of authority, then anything can happen.”

Now there is a more meaningful hat trick — marriage, children, dogs. In a word: stability. And access to stories that use the great knowledge of people she’s acquired along the way as a precious asset. You see that in this novel; she can leap nimbly from fear to scorn to grief to comedy, doesn’t shrink from politics and racism, and still can include a love story that’s not a digression. This is the kind of novel in which the author has everyone’s number, starting with her own.

The story bounces around. Bad choices, wrong turns, dark irony dot the ride. And when it gets to the end, Boyd delivers a sentence so quiet you have to shake your head in wonder. And when was the last time you heard a writer say, “My goal is to go to bed at night feeling like I’m part of what’s good in the world. When I got clean I went in a flash from being dangerous to colorful, from being part of the problem to being part of the solution. I feel like God’s final joke is that I’ve turned out to be such a happy functional person.”

“Tomb of the Unknown Redneck” is the punch line of that joke.